Buddenbrooks, 1923

In 1923, Buddenbrooks became the first Thomas Mann novel to be adapted for film. Albert Pommer was the producer and Gerhard Lamprecht directed. Although Thomas Mann had ‘every confidence in the seriousness’ with which screenwriters Luise Heilborn-Körbitz and Alfred Fekete ‘approached the project,’ he was aware that a film adaptation of the novel in the strict sense of the word would be virtually impossible, because "it will probably be impossible to truly convey the novel in images, and I had to agree when I was told they wanted to limit themselves fundamentally and explicitly to producing a film “based on motifs” from Buddenbrooks.‘ Thomas Mann therefore agreed to a free adaptation, although he was concerned that the film might end up being ’literary and artistically botched".

Thomas Mann was very critical of the film in private. He could not express his opinion publicly, as this would have jeopardised the financial success in which he had a percentage share. In a letter to Ernst Bertram dated February 1923, he wrote: ‘A Berlin export company is managing Buddenbrooks, having a stupid and sentimental cinema drama “based on motifs from it” put together, of which my soul knows nothing, but for which there is a great deal of interest in Scandinavia, Holland and America [!], and which has earned me a lot of money and will continue to do so.’

The distance between the film and its source material is obvious. However, it would be short-sighted to conclude that this means it is simply a bad film. The adapters reduced the source material to individual parts and plot elements, sacrificing the novel's essential themes and messages. Of the four generations, only one remains: the siblings Tony, Thomas and Christian. The half-century covered by Thomas Mann's novel has been reduced to a single episode around 1880: a grain deal between the Buddenbrook family and the Lübeck Senate. And there is little sign of the theme of decline: neither the business nor any member of the family dies. The authors drew on the available material, not to string together set pieces, but to create a new, coherent work. The impression of distance from the original is reinforced by the fact that the film's plot has been moved to the present day of the 1920s. The film is not a literary adaptation in the strict sense, but rather a critical reading of the original.

The leading roles were played by the well-known silent film stars Peter Esser (Thomas), Mady Christians (Gerda) and Alfred Abel (Christian). The film premiered on 31 August 1923 at the Tauentzienpalast in Berlin. Although Thomas Mann was not happy about this project, the film was very well received by contemporaries. Many of the reviews began with the fundamental statement that a film should be judged independently of any existing source material. The assessment gratefully followed the filmmakers' statement that they had produced a film ‘based on motifs from the novel.’ Not least because of this, the film was to be regarded as a prime example of literary adaptations, because it was not actually an adaptation at all. The filmmakers had concentrated on individual parts of the novel and constructed an exciting plot from them, happily selecting what was suitable for the film. The majority of critics saw such a respectful distance that the book did not suffer any damage as a result of the adaptation, and at the same time a film was created that was a very good film when viewed only against the background of the laws of its medium: ‘To the book what belongs to the book, and to the film what belongs to the film,’ wrote the Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger.

The reviews were favourable about the plot and the quality of the artistic and technical work. The dramaturgy and film aesthetics attempted to break new ground in this film, with the visual language in particular being described as successful. Where shortcomings were identified, they were not attributed to the film, but to the source material: ‘A little anaemic – but isn't that also true of Thomas Mann?’

Lamprecht's melodrama offers a glimpse into early German cinema, and thanks to an excellent ensemble cast, he has succeeded in creating a respectable film, which, of course, cannot be measured against the novel.

When watching this film, one should always remember that it is a product of the then still young medium of film. Reflections and refractions of the plot through shots in mirrors or windows were innovative in 1923. The portrayal or interpretation of female roles may still seem revolutionary to us today. The film reveals itself to be a child of its time when it allows its female characters to appear with a new female self-image.

The Buddenbrooks

Germany 1923, Director: Gerhard Lamprecht, 106 min, English subtitles, Age rating: 0

Buddenbrooks, 1959

The 1959 film adaptation of Buddenbrooks was originally a two-part cinema film. The first part was 99 minutes long, the second 107. Later, a version was released that had been edited down to 145 minutes. The idea of adapting the novel for film a second time had been around since 1954. Thomas Mann wanted this project to be an all-German production. This was the premise when the rights to Buddenbrooks were granted. However, this also became a problem. During the Cold War, DEFA managed to find a West German film distributor willing to cooperate, but this company considered it advisable to have this German-German project approved by the government in Bonn.

The Adenauer government refused to give its approval, arguing that the co-production would ‘open up a new avenue for communist infiltration.’ The politicians' concerns were enough for the West German film distributor to withdraw from the project. The project had failed and Thomas Mann was very disappointed. He did not live to see the second attempt.

Producer Hans Abich attempted to do so in early 1956, acquiring the film rights from Thomas Mann's heirs in collaboration with DEFA. Abich wanted to ignore the opinion from Bonn, but found that political resistance made it impossible to finance the project. Ultimately, this ambitious project also failed. The co-production agreement was dissolved, with the rights being granted separately – for East and West – by the community of heirs. The Buddenbrooks film made in 1959 is a West German production; the East German side did not make use of the film rights.

Erika Mann collaborated as co-author on this new Buddenbrooks film. She also lent her voice to Josephus, the parrot belonging to the dentist Dr. Brecht. She was responsible for approving the final version of the screenplay. Filming began in June 1959 and was completed on 10 September. The first part of the film adaptation premiered on 11 November in Lübeck's Stadthalle in front of 1,200 visitors and in the presence of Katia and Erika Mann.

Critics reacted cautiously to the film. Although it adhered more closely to the original than the 1923 adaptation, its attempt to convey the novel's key messages and themes was considered only partially successful. It was clear that cuts had to be made, but there was considerable disagreement about how this should be done. The reduction of the sophisticated literary source material to its trivial elements and the narrowing of the plot to the ‘cosiness of a touching family story’ were criticised. Well-known key scenes were focused on, while the inner developments of the characters were ignored to such an extent that critics got the impression that ‘the film was not meant to be taken seriously’. For some, ‘Thomas Mann had become a Hanseatic Ganghofer overnight,’ as the Abendpost wrote.

Critics even spoke of falsification. However, those who are unfamiliar with the book will not notice the falsification. The plot is coherent and the basic features of the story of decline are preserved.

In the critical reception, the film suffered above all from the fact that reviewers assessed the novel first and the film second, in keeping with the motto of the Westdeutsches Tageblatt: "If the writer Thomas Mann and his novel did not exist, the film would be easier to appreciate." Perhaps one should rather see it as Thomas Mann did in 1954: "My book is not a film – the film is not my book. One should avoid comparisons if at all possible! And if comparisons must be made: then not film with book, but film with other films." The film has always been popular with audiences, not least because of its cast, whose roster reads like a who's who of German cinema in the 1950s: Hansjörg Felmy, Nadja Tiller, Liselotte Pulver, Hanns Lothar, Werner Hinz, Lil Dagover, Walter Sedlmayr, Maria Sebald, Helga Feddersen, Günther Lüders, Gustav Knuth and Horst Janson.

Buddenbrooks, 1979

The third film adaptation of Buddenbrooks, directed by Franz Peter Wirth, triggered a real Mann boom. After several years of preparation, filming began in the spring of 1978 for what was then Hessischer Rundfunk's most expensive production to date (cost: DM 12.5 million). As an eleven-part television series, it attracted over 15 million Germans to their television screens in autumn 1979 (viewing figures of 43%!) and sparked a new interest in Thomas Mann, because, as the press wrote, the series apparently ‘captured the spirit of the book and the idiosyncrasies of the situation and characters’, and the novel's characters were portrayed almost true to the work thanks to careful casting. Viewers appreciated that no attempt was made to ‘desperately create a certain “contemporaneity” in line with fashionable historical interpretation.’ Parallel to the broadcast, the Hamburger Abendblatt ran a series entitled ‘The World of the Buddenbrooks’ over several weeks, which focused on the historical background to the film's plot. Television viewers were provided with summaries of the novel and family trees in magazines. Energetic journalists made their way to Lübeck to prove that Buddenbrooks still stirred people's emotions, just as it had immediately after the novel's publication.

Martin Benrath was cast as Jean Buddenbrook and Ruth Leuwerik, who had taken on a role for the first time in 15 years after a hiatus from film, as the consul. Volker Kraeft played Thomas, Reinhild Solf played Tony Buddenbrook (Mario Kracht played the young Tony), and Michael Degen played Grünlich. Other roles included Klaus Schwarzkopf as banker Kesselmeyer and Rolf Boysen as pilot commander Schwarzkopf. Gerd Böckmann, who played Christian, had the difficult task of competing with the shadow of Hanns Lothar, who had excellently embodied the character in 1959.

Critics saw the series as a costume drama. Although the attention to detail in the set design was praised, overall it was described as ‘magnificently photographed boredom’. Some reviewers saw Buddenbrooks as the German answer to the English series Upstairs, Downstairs. Director Franz Peter Wirth seemed to follow this tradition when he said: ‘We definitely don't want to deliver an exaggerated literary adaptation, but entertainment in the best sense of the word.’ As in previous adaptations, great importance was attached to the visuals and acoustics, but ‘sometimes this great television film got bogged down in beautiful photography’. Absolute fidelity to the original work was not welcome, because ‘scripts do not become more cinematic by parroting the books,’ criticised Der Spiegel. In general, however, this adaptation lacked Thomas Mann's most important stylistic device: irony. ‘Either irony cannot be shown on screen, or the director was unable to reveal it [...],’ wrote Die Welt. Critics emphasised the deviation from the original and the finding of new paths in every film adaptation. Despite all the criticism, viewers liked it. The series was one of the most internationally successful German TV productions; it was sold to twelve European countries. In 1984, it was broadcast by PBS in the USA in the series ‘Great Performances’, which is reserved for outstanding television productions.

The Mann family also liked the series, with Golo Mann speaking on behalf of the heirs and expressing his positive opinion of the adaptation: ‘Of all the film adaptations of novels that I have seen, this is by far the most faithful.’

In an interview, Franz Peter Wirth said that he and his team would have achieved a great deal ‘if we can encourage even a fraction of the viewers to read the novel again’. He can be credited with this success. The sales success of the edition of Buddenbrooks at the time proves this.

Buddenbrooks, 2008

Heinrich Breloer earned his Thomas Mann spurs in 2001 with the docudrama Die Manns – Ein Jahrhundertroman (The Manns – A Novel of the Century), a three-part television film about the life of the Mann family, which was very successful and won numerous awards. After the Manns, Breloer, who holds a doctorate in literature, turned his attention to Buddenbrooks and shot the fourth German film adaptation in the summer of 2007. As with previous adaptations of the novel, many well-known German actors were cast. The driving force was Armin Mueller-Stahl, who played Thomas Mann in Die Manns. Here he was Jean Buddenbrook, with Iris Berben playing the Consul's wife at his side. The three children were played by Jessica Schwarz, Mark Waschke and August Diehl – all three are now very well-known actors who also work internationally. Alexander Fehling played Morten Schwarzkopf, Lübeck-born Justus von Dohnányi Grünlich, and Sylvester Groth played Kesselmeyer. As with Die Manns, the screenplay was written by Heinrich Breloer and Horst Königstein. Cinematographer Gernot Roll was also responsible for the images in the 1979 Buddenbrooks series.

After an intensive period of preparation, the first take for Buddenbrooks began in Lübeck on 31 July 2007, as the decision had been made early on that the film would be shot largely at the original locations in Lübeck. ‘A city is making a film,’ is how Heinrich Breloer described the enthusiasm and support of the people of Lübeck. Filming took place over a total of 70 days until mid-November, in Lübeck and the surrounding area, in Augsburg, Munich, Bruges and in a studio in Cologne.

The Hanseatic city proved to be a place that was very easy to transport back in time, with ideal locations for outdoor filming – because a surprising number of streets have been almost completely preserved or renovated. Of course, the Buddenbrookhaus at Mengstraße No. 4 played a central role in the film adaptation. From the outset, it was clear that a replica of the entire three-storey Buddenbrookhaus in the studio in Cologne would produce the best cinematic results. However, the exterior shots were filmed on location in Lübeck. Heinrich Breloer noted: ‘When we were filming in front of the Buddenbrookhaus, we sometimes had the feeling that we were filming in a large studio – the “Lübeck Open-Air Studio” was a location where we were able to work excellently.’

The film premiered on 16 December 2008 at the Lichtburg cinema in Essen; on 19 December, there was a screening of the film in the presence of the director and the leading actors at the Lübeck Stadthalle.

The film, which has a running time of 150 minutes, as well as the 30-minute longer television version, which was shown on Arte and ARD in December 2010, met with lively public interest. However, as with every Thomas Mann adaptation, film critics were only moderately enthusiastic. The sets and costumes in this adaptation were even more opulent than in the television series; ‘everything is designed to overwhelm’. The landscapes and, above all, the city were depicted in a very picturesque manner. While many critics saw the film as (once again) a mere illustration of the novel, lacking existential depth and subtlety, and described the director as overly detail-oriented, the Neue Zürcher Zeitung newspaper felt that the emphasis on visual appeal was in keeping with the novel. Because Heinrich Breloer said he wanted to give Thomas Mann a classic literary adaptation, he was naturally measured directly against the novel. No reviewer measured the Buddenbrooks adaptation against other German films of the time. The Frankfurter Rundschau found the production ‘all in all not bad at all’, but stiff and model-student-like; nevertheless, it was enjoyable to watch thanks to the cheerful actors. Once again, as with previous film adaptations, the cuts and changes to the content were lamented. Although the novel's leitmotifs were well translated into the medium of film, the style was too simplistic and the film showed too much directly. The reviews often asked whether this further film adaptation was necessary. This is a question that arises with every Thomas Mann film adaptation, because ‘bringing a work by Thomas Mann to the screen is always an artistic risk’. But, as one reviewer of Breloer's Buddenbrooks film noted: ‘Incidentally, I know what I'll be reading over Christmas, and the fact that this film not only encourages but downright provokes me to do so is probably the best thing a literary adaptation can achieve.’ Thomas Mann is right when he says: ‘The book remains. It will not be read any less because of the film, probably even more.’

Tonio Kröger, 1964

The novella Tonio Kröger was published in 1903, and Thomas Mann called it his ‘favourite literary child’. Alongside Death in Venice, he always considered it one of his major works, placing it on a par with his great novels. In 1930, he said, ‘Of all the things I have written, it is perhaps closest to my heart.’ What pleased him was the fact that the novella repeatedly appealed to young people – because they recognised themselves in it.

Remarkably, interest in filming Tonio Kröger first came from Italy. In September 1960, Italian producer Emanuele Cassuto acquired the rights from Thomas Mann's estate. However, the granting of the rights was linked to a number of agreements. The film was to be produced in Germany, and the screenplay was to be written by Ennio Flaiano, faithfully based on the novella and in consultation with Erika Mann, in an Italian version. Erika Mann was to write the German screenplay and also be present during filming.

In the end, however, it became a German-French co-production. It was directed by the German Rolf Thiele, who also filmed Thomas Mann's story Wälsungenblut a year later. The French insisted on casting Jean-Claude Brialy, a well-known actor in France, in the role of Tonio Kröger, which was originally intended for Maximilian Schell. Nadja Tiller was also cast because of her popularity. She had already appeared in the 1959 film adaptation of Buddenbrooks, where she played the character of Gerda Buddenbrook.

Ennio Flaiano was a renowned Italian screenwriter. He collaborated frequently with Federico Fellini, writing the screenplays for 8½, La dolce vita and La Strada, among others.

The film's highly acclaimed cinematographer was Wolf Wirth. In the 1960s, he was responsible for the images in several literary adaptations, including Heinrich Böll's Das Brot der frühen Jahre (The Bread of Early Years, 1961), Thomas Mann's Wälsungenblut (The Blood of the Walsungs, 1965) and Grass's Katz und Maus (Cat and Mouse, 1967). He gave the film a special aesthetic touch with reflections and flashbacks and attempted to translate Thomas Mann's words symbolically.

The young Tonio Kröger was portrayed by Mathieu Carrière, who launched his acting career with this film adaptation. He was discovered by Rolf Thiele in the schoolyard of the Katharineum at the age of 13 and immediately hired for the role of the young Tonio. Two years later, he gave a brilliant performance in the film adaptation of Musil's The Confusions of Young Törless.

The supporting roles in the film were also played by top-class actors: Werner Hinz played Tonio's father, Gert Fröbe played the policeman who is supposed to arrest Tonio as an impostor. Walter Giller was the man who philosophises about the ‘stars’ on the crossing to Denmark, and Günther Lüders was the librarian at the public library located in Tonio's old family home. Theo Lingen was incomparable in his role as dance teacher Knaak.

Filming took place from 27 January to 1 May 1964 in Lübeck, Munich, Florence and Skagen, Denmark, including locations in Lübeck such as the town hall and the Buddenbrookhaus.

The film premiered in Venice on 31 August 1964 as the official German contribution to the Biennale. On 2 September, it was shown at a grand celebration in Lübeck as part of its German premiere. It was also screened at the Berlin Film Festival as Germany's competition entry. Rolf Thiele was nominated for the Best Director award in both competitions.

Critics' reviews of the film were mixed, ranging from masterpiece to misstep. There was unanimous praise for the cinematography, and the actors were also praised, with the exception of Nadja Tiller, who proved to be miscast. The director was also criticised. The general opinion was that the film was an improvement on other German productions in recent years, but that it did not do justice to Thomas Mann.

Little Mr Friedemann

At the end of the 1980s, GDR television dramaturge Eberhard Görner presented Golo Mann with a detailed screenplay for a film adaptation of Little Mr Friedemann, which the poet's son reviewed very positively. The novella was first published in 1897 and is one of Thomas Mann's earliest stories. Following the positive response from the Mann family, filming began in 1990 in Lübeck, Ratzeburg, Wismar and Potsdam under the direction of Peter Vogel, one of the most famous directors in the GDR. The film project ran into problems because, following the dissolution of the GDR, no one knew how the film would ultimately be financed or which broadcaster would air it. The film is one of the last DEFA projects to have been shot in the GDR. The premiere took place on 4 February 1991 at the Capitol Cinema in Lübeck, attended by screenwriter Eberhard Görner and Maria von Bismarck, who played Gerda von Rinnlingen. The film was shown on ARD on 29 March 1991.

The main role of Johannes Friedemann was played by Ulrich Mühe. The actor, who grew up in the GDR and sadly passed away in 2007, became internationally known in 2006 through the Oscar-winning film The Lives of Others.

Screenwriter Eberhard Görner worked as a dramaturge and author for East German television from 1970 to 1990, where he was co-author and founder of the successful series Polizeiruf 110, among other things. From 1991 onwards, Görner worked as editorial director and writer at Provobis Film- und Fernseh GmbH, where he was responsible for documentaries and literary adaptations. In 1997, he also made a documentary about Elisabeth Mann Borgese. Görner had accompanied Thomas Mann's youngest daughter at home and at university.

Eberhard Görner worked on many film projects with director Peter Vogel; they often collaborated on Polizeiruf 110 in particular. Before Little Mr Friedemann was filmed, Vogel and Görner adapted Christa Wolf's novel Selbstversuch for television, which was broadcast in January 1990. Peter Vogel still works extensively for television today. He has directed several episodes of the crime series Tatort, as well as episodes of Alarm für Cobra 11 and In aller Freundschaft.

The story Little Mr Friedemann has numerous autobiographical features in terms of its characters and props, and in many respects is set in a world that anticipates Buddenbrooks. Lübeck is unmistakable, even though the name of the hometown is not mentioned: there is the grey gabled house with its landscape room, there are the city walls, the city theatre and the old schoolhouse with its Gothic vaults. Friedemann's father is a Dutch consul, and the character of Friedemann himself is, at least outwardly, modelled on a cousin of Thomas Mann's from Lübeck who had a hump.

A comparison between the novella and the film shows that the main plot line is the same in both stories. The two main characters were also portrayed in the film as Thomas Mann had intended. However, they were given additional characteristics that are not found in the novella, but which do not contradict it either. Thus, the film provided interesting interpretative aspects. The film's shortcoming, however, was that it sometimes referred too closely to the novella. Viewers who are unfamiliar with Thomas Mann's story will be confused because they lack context and cannot properly understand the details. The film adaptation attempted to use cinematic techniques such as camera movement and perspective to convey both the inner lives of the characters and the narrative perspective in a way that approximates Thomas Mann's linguistic artistry. The use of leitmotifs and irony also shows that the film closely follows the narrative.

Felix Krull, 1957

An unusually short time after the novel's publication, The Confessions of Felix Krull, Confidence Man was made into a film. The book, subtitled The First Part of the Memoirs, was published in September 1954 after several fragmentary pre-publications. Before his death in August of the following year, Thomas Mann had the opportunity to read the exposé on the planned film adaptation, written by Robert Thoeren on behalf of Filmaufbau Göttingen. His daughter Erika recalled his reaction: He was in the best of spirits. ‘Very nice!’ he said, and ‘What a film-maker can come up with!’ The second remark referred to the ending, the ‘finale’ freely invented by Thoeren.

Filmaufbau acquired the rights to adapt the novel for the screen in November 1955 (three months after Thomas Mann's death) from Thomas Mann's heirs for DM 80,000. Erika Mann oversaw the film's production and contributed to the screenplay. She ultimately took on a small role in the film herself, playing the governess Eleanor Twentymans.

Kurt Hoffmann was hired to direct the film adaptation of Krull. The cast is a select group of popular actors. The young Horst Buchholz plays the title role. Other big names such as Heidi Brühl, Liselotte Pulver, Heinz Reincke, Peer Schmidt and Paul Henckels also contributed to the high expectations. The producers were well aware of the special responsibility that the lead actor Horst Buchholz had for the success of the film – and they convinced the critics: ‘An actor plays a person who has no character at all, but who slips from one mask to another! And in fact, this behaviour, which is exclusively geared towards external effect, seems to be part of Horst Buchholz himself,’ wrote the Frankfurter Rundschau afterwards.

Confidence in the production was also high because Hans Abich was in charge of overall management. Abich knew that film adaptations of literature are more susceptible to criticism than films based on original manuscripts because they always have to stand up to comparisons with the original work. He argued defensively: ‘Of course, we will not be able to compare ourselves to the poet in the end. However, we want to look forward with a degree of impartiality to retelling the story of Felix Krull in its filmable parts to all those who have not read the novel themselves.’

The public interest that accompanied the film's production was fuelled by sensationalist reporting on court cases involving the Krull film. Hollywood-based writer John (Hans) Kafka filed a copyright lawsuit and attempted to prevent the film's release by means of a preliminary injunction. His accusation: Thomas Mann had taken the idea of identity exchange from his novella Welt und Kaffeehaus (World and Coffee House), published in 1930 in Münchener Illustrierte, and thus appropriated his intellectual property. At first glance, the accusation of plagiarism proved untenable; it was quite obvious that this was a clever publicity stunt by Kafka, who was prepared to withdraw his lawsuit if his name appeared in the film's opening credits and the film company compensated him with 20,000 to 30,000 DM.

On 20 May 1957, the 17th Civil Chamber of the Berlin Regional Court dismissed Kafka's lawsuit. Thomas Mann's widow Katia had previously made a sworn statement in which she assured that the role reversal had been part of the concept of Felix Krull as early as 1909. Filmaufbau was able to avoid compensation claims and legal costs and ultimately benefited from the lawsuit over its ‘plagiarised film’ because it gave it additional media coverage.

Despite this turmoil, which was closely followed by the press, the film premiered on 25 April 1957 at the Gloria-Palast in Berlin and the Lichtburg in Essen after only three months of production and 32 days of filming, in the presence of Katia and Erika Mann.

After the premiere, it quickly became apparent that the film would be a lasting success with audiences. The verdict of the daily press, on the other hand, was ambivalent. The ending of the film was particularly debated: ‘It stems from a completely Krull-like fantasy. The miraculous rescue by the apparent death poison is an idea that seems a little like the Count of Monte Cristo accidentally appearing in The Magic Mountain [...].’

Some critics reconsidered and set the book aside for a moment. ‘Despite all the ifs and buts, this film remains a highly amusing variation on a literary delicacy.’ And finally, a summary: ‘But even so – once all objections have been mentioned – it is a very tasteful, tactful, highly amusing film’ – and that was certainly what the film's creators had aimed for; no more and no less.

Felix Krull has become a classic of German cinema. It won the German Film Award in 1957 and even received a Golden Globe for Best Foreign Language Film in America in 1958.

The Magic Mountain, 1982

A young man from Hamburg named Hans Castorp, almost 23 years old, visits his cousin Joachim Ziemßen, who is suffering from tuberculosis, at the health resort in Davos. When the visitor is diagnosed with lung disease shortly before his departure, Hans Castorp also becomes a patient. He stays, and in the end he remains for seven years, from August 1907 until the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914.

Hans Castorp's search for self-realisation in this web of meaning between life and death is a theme that is difficult to convey through cinematic means; in fact, it was considered unfilmable, as too much abstract dialogue, too little action and a weak hero do not necessarily facilitate a cinematic representation. But as early as 1928, a film adaptation of The Magic Mountain was being considered. Thomas Mann said: ‘If approached boldly, it could be a remarkable spectacle, [...] But it will be abandoned. The task is too demanding, both intellectually and materially.’

Over the years, there were several attempts to get a film project based on The Magic Mountain off the ground. Names such as Luchino Visconti and Peter Zadek were discussed as possible directors. Finally, in 1980, Franz Seitz decided to tackle a film adaptation of the novel. He had just produced the successful film adaptation of The Tin Drum and was the producer responsible for three other Thomas Mann film adaptations (Tonio Kröger, Wälsungenblut and Disorder and Early Suffering). Hans W. Geißendörfer (later known as the producer of Lindenstraße) took over the direction and also wrote the screenplay.

In the summer of 1980, the conditions for filming were established and the film crew assembled. Thanks to a collaboration with ZDF, there were two versions of ‘Zelluloid-Zauberberg’: a 153-minute cinema film and a three-part television series, each episode lasting 105 minutes. The film was released in cinemas in February 1982, and the television version was shown in April 1984.

Filming began in January 1981 and lasted 100 days, spread over six months. The film was made with a budget of DM 20 million, making it one of the biggest German film productions of its time.

Geißendörfer's team included cameraman Michael Ballhaus, among others. He began his career with Rainer Werner Fassbinder and was one of the world's best in his field. He shot Hollywood films such as Gangs of New York and worked with directors such as Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola and, time and again, Wolfgang Petersen.

Swiss film architects Heidi and Toni Lüdi were responsible for the set design, whose first challenge was to find a suitable film location for the main setting. The Bellevue forest sanatorium described by Thomas Mann in his novel had since been modernised, like many other Swiss spa hotels. By chance, a slightly renovated grand hotel was found in the former climatic health resort of Leysin. The hotel was extensively redesigned for filming; important interior locations such as the dining room and the salon were recreated in a Berlin studio.

The set designers strove for accuracy in every detail of the production, researching museums, antique shops and artisans to find suitable props. The costume designers scoured flea markets in London, Vienna and Paris for costumes.

The international cast was partly due to the German-French-Italian co-production of the film, but also to reflect the international character of the sanatorium. French actress Marie-France Pisier, who also appeared in films by François Truffaut, was cast as Madame Chauchat, Italian actor Flavio Bucci as Settembrini and Charles Aznavour as his adversary Naphta. Hans Christian Blech can be seen as Hofrat Behrens and Alexander Radszun as Joachim Ziemßen. One of the big names in the film is the American Rod Steiger as Mynheer Peeperkorn. The role of Hans Castorp, on the other hand, was cast by Geißendörfer with the then unknown theatre actor Christoph Eichhorn (his father Werner Eichhorn was the narrator in the film). Many supporting roles were also filled by prominent actors: Margot Hielscher, Kurt Raab, Rolf Zacher and Tilo Prückner are just a few names. A total of more than 4,500 extras appeared in the film.

The film won the German Film Award in silver in 1982; the set designers, the Lüdis, received the Film Award in gold, and in 1983 the film was honoured with the Bavarian Film Award.

The set designers were also praised by the press for their success in bringing the special atmosphere of the luxury sanatorium to life. On the other hand, the idiosyncratic abridgements and interpretations of the work were criticised: "Of course, the result is nothing more than a digest of this thousand-page novel, but it is nevertheless worth watching and considering. A respectable adaptation of this mountain of a novel." The more detailed, almost six-hour television version is more recommendable.

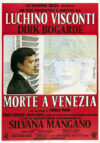

Death in Venice

Alongside Tonio Kröger, Death in Venice is one of Thomas Mann's best-known stories and is often mentioned in the same breath as his novels. The text was published in autumn 1912.

As early as 1934, there were initial plans to adapt the novella for the screen. Numerous filmmakers were interested in the material, including John Huston and José Ferrer. However, the projects always failed because a major film studio would only finance them if the boy had been turned into a girl.

The renowned Italian theatre and film director Luchino Visconti not only passionately admired Thomas Mann throughout his life, he also saw himself as a contemporary. Although born in 1906, he felt he belonged ‘to the era of Thomas Mann, Marcel Proust and Gustav Mahler’. He was able to persuade the producers to accept a screenplay that retained the basic story.

During the winter season of 1969/70, the Grand Hotel des Bains on the Lido underwent extensive renovation and was restored to its former glory; the hotel scenes were then filmed from March to mid-May.

Visconti did not cast a big star as Aschenbach, but rather the English character actor Dirk Bogarde. He auditioned hundreds of young amateur actors until he found the perfect Tadzio in 14-year-old Björn Andresen from Stockholm. And finally, with his typical meticulousness, he employed legions of costume and set designers to resurrect the Belle Époque in Venice and on the Lido.

The artistic device of choosing compositions by Gustav Mahler to support the elegiac images leads to one of the most successful translations of language and literature into images. And in another artistic device, the writer Aschenbach became a composer in the film. Thomas Mann borrowed the first name Gustav from Gustav Mahler and modelled his main character's appearance on the composer. But Mahler was not the only model for the film's Aschenbach. Visconti used the composer character Adrian Leverkühn to make the artist's predicament understandable. In dialogue flashbacks, Aschenbach and his friend Alfried discuss their different views on artistic creation. These statements were taken from Doctor Faustus. The ship on which Aschenbach reaches Venice is called ‘Esmeralda’.

Just two months after the film's German cinema release, the classical music label Deutsche Grammophon released the Adagietto from Gustav Mahler's Fifth Symphony and the Misterioso from his Third Symphony under the title ‘Death in Venice’. The music was appropriated by the novella, but in return, the novella was also appropriated by the music.

The film is more than just another adaptation of a literary work, because Visconti recreated the story by retelling it in his film. In doing so, he went beyond a mere illustrated retelling of the original text, because he had read Thomas Mann and left him behind in order to take control of the material himself.

Visconti's film stands out from all others thanks to his masterful handling of the literary source material on the one hand and his extraordinary flair for the use of cinematic techniques on the other. The director succeeded in adequately translating Thomas Mann's multifaceted language into the medium of film using the aesthetic means of image and sound. Thus, spoken language is completely withdrawn (only a quarter of the film features dialogue), leaving the ‘speaking’ to the music. And instead of an omniscient narrator, there is the all-seeing camera. Visconti recreated the rich and precise character and situation descriptions that Thomas Mann achieves with his language through the images, the set design, the actors and the precisely coordinated movements of the camera and the actors.

Morte a Venezia, as the film is called in the original, premiered in London on 1 March 1971. In May 1971, the director took the film to the Cannes Film Festival and received a special award. It was shown in West Germany on 4 June 1971, but not in East Germany until 1974.

For the first time, reviews of a Thomas Mann film adaptation focused not on the content, but on what makes the film what it is: image and sound. The music creates cross-references, comments on the film's events and thus develops its own meaning. The film was praised for what had often been criticised in other film adaptations: its relevance to the present. It was a film that, despite its historical accuracy, revealed a modern sensibility. And finally, people were beginning to compare the film not only to the literary source material, but also to other films.

Thomas Mann's sons Golo and Michael Mann spoke very favourably about the film and were of the opinion that Thomas Mann would have been delighted.

Visconti's film set new standards – in terms of literary adaptations and Thomas Mann adaptations in particular. Everything that came after Death in Venice is based on what remains the most successful Mann adaptation, whether the film is quoted or deliberately ignored. Since then, there have actually been two Death in Venices, that of Thomas Mann and that of Luchino Visconti, which exist side by side as equals.

Mario and the Magician

The idea of adapting the novella Mario and the Magician for the screen arose early on. Thomas Mann himself had hoped for a film adaptation as early as 1931, just one year after its publication – and for a generous contract: ‘10,000 dollars for the worldwide film rights must surely be the minimum,’ he wrote to his publisher. Luchino Visconti also pursued the plan of a film adaptation long before he filmed Death in Venice in 1971. However, the film never materialised, and instead Visconti staged Mario as a ballet at La Scala in Milan in 1956.

In 1988, Jürgen Haase acquired the film rights and approached Klaus Maria Brandauer. Haase pursued an elaborate international co-production with production companies and television stations from Germany, Austria and France, with a budget of DM 17 million (which was ultimately exceeded by five million). Stars from various countries were brought in to guarantee international interest: Julian Sands from Britain, Anna Galiena from Italy, Philippe Leroy-Beaulieu from France, and Rolf Hoppe and Elisabeth Trissenaar from Germany.

For Klaus Maria Brandauer, however, there also seemed to be a political necessity to make the film at that time, because in the early 1990s, a whole series of xenophobic attacks shook the nation in Germany. At the time, it seemed as if xenophobia was the ugly flip side of the euphoria surrounding German reunification, both in the new and old federal states. In Austria, right-wing populist Jörg Haider stepped into the limelight, and then, while the film was still in production, Silvio Berlusconi came to power in Italy in March 1994. Never before had a film adaptation of Mario's story seemed more topical and meaningful.

Although conceived from the outset as a historical adaptation, with the film set in the year 1926 as described by Mann, everyone involved in the film agreed that current events had to be incorporated. And for director Brandauer, this was a prerequisite for adapting the material at all: ‘It has to mean something to people today. There have to be similarities, contemporary variations on the theme, otherwise we won't be interested in it.’

However, in order to give the film a moral and political message, the plot had to deviate significantly from the original story at one point. According to Brandauer's credo, literature cannot be adapted one-to-one: ‘You have to film it with a certain degree of irreverence.’ Consequently, the opening credits and film posters stated ‘Freely adapted from the story by Thomas Mann’.

Implementing this concept coherently proved no simple task. There were several versions of the screenplay before Brandauer was satisfied with one. The script also introduces changes to the characters. The family, unnamed in the novella, is called "Fuhrmann" in the film. The husband of Signora Angiolieri, to whose guesthouse the Fuhrmanns relocate, is by no means the inconspicuous, insignificant figure he was in the literary source. Rather, he is the town's new prefect, embodying the authoritarian state of the Duce – complete with all the clichés of power that cinema typically employs for such potentates: polished boots, trained dogs.

Brandauer summarised the intention behind the Mario film as follows: "I'm not interested in the potentates and the seducers; I'm interested in the people who allow themselves to be seduced. The Fuhrmanns – that's us."

After the film opened in cinemas on 15 December 1994, reviews were critical and disappointed.

The Tagesspiegel remarked: "Even if Brandauer claims that one-to-one literary adaptations do not exist and should not exist, the disfigurement of a novella naturally makes no sense either." The Film-Dienst noted that, despite certain weaknesses, the film was convincing "as an evocation of an era in upheaval, raising questions about seduction and susceptibility, xenophobia and intolerance that remain as relevant as ever."

The film suffered above all from the director placing too much emphasis on himself as the lead actor. No one disputed Brandauer's acting quality, yet the film devolved into a one-man show, for "only the magician ignites any passion in the images. The more insignificantly the other characters are staged, the more charisma Cipolla radiates. Nothing can compete with his dazzling ambiguity. This benefits Brandauer the actor. But it harms Brandauer the filmmaker, and it paralyses his film."

Despite the harsh criticism in Germany, the film proved to have its merits. In 1995, Brandauer was honoured for his role as Cipolla at the Moscow International Film Festival, and cinematographer Lajos Koltai was recognised for his work.

What remains after seventy years of Thomas Mann adaptations? Critics have consistently struggled with these films, demanding fidelity to the source while simultaneously lamenting its limitations, celebrating independent interpretations one moment and branding them distortions the next. Thomas Mann himself articulated his position early on: "My book is not a film – the film is not my book." That Visconti's Death in Venice stands alone as an unqualified masterpiece is surely because the director followed this principle most consistently: he did not film the text but created an independent work of art capable of standing alongside the novella. All other adaptations have achieved at least one thing: as Franz Peter Wirth had hoped, they have repeatedly led new readers to Thomas Mann's books. Perhaps that is all a literary adaptation can truly aspire to accomplish.

About the author

Britta Dittmann studied literary studies and art history in Kiel. Since 1998, she has been a research associate at the Cultural Foundation of the Hanseatic City of Lübeck and is responsible for the library and archive of the Buddenbrook House. She is Vice President of the Heinrich Mann Society.